“These violent delights have violent ends”

Here’s the complete article which appeared in the Romeo & Juliet Souvenir Programme

Our Co-Founder Matt Pinches considers the violence in Romeo & Juliet…

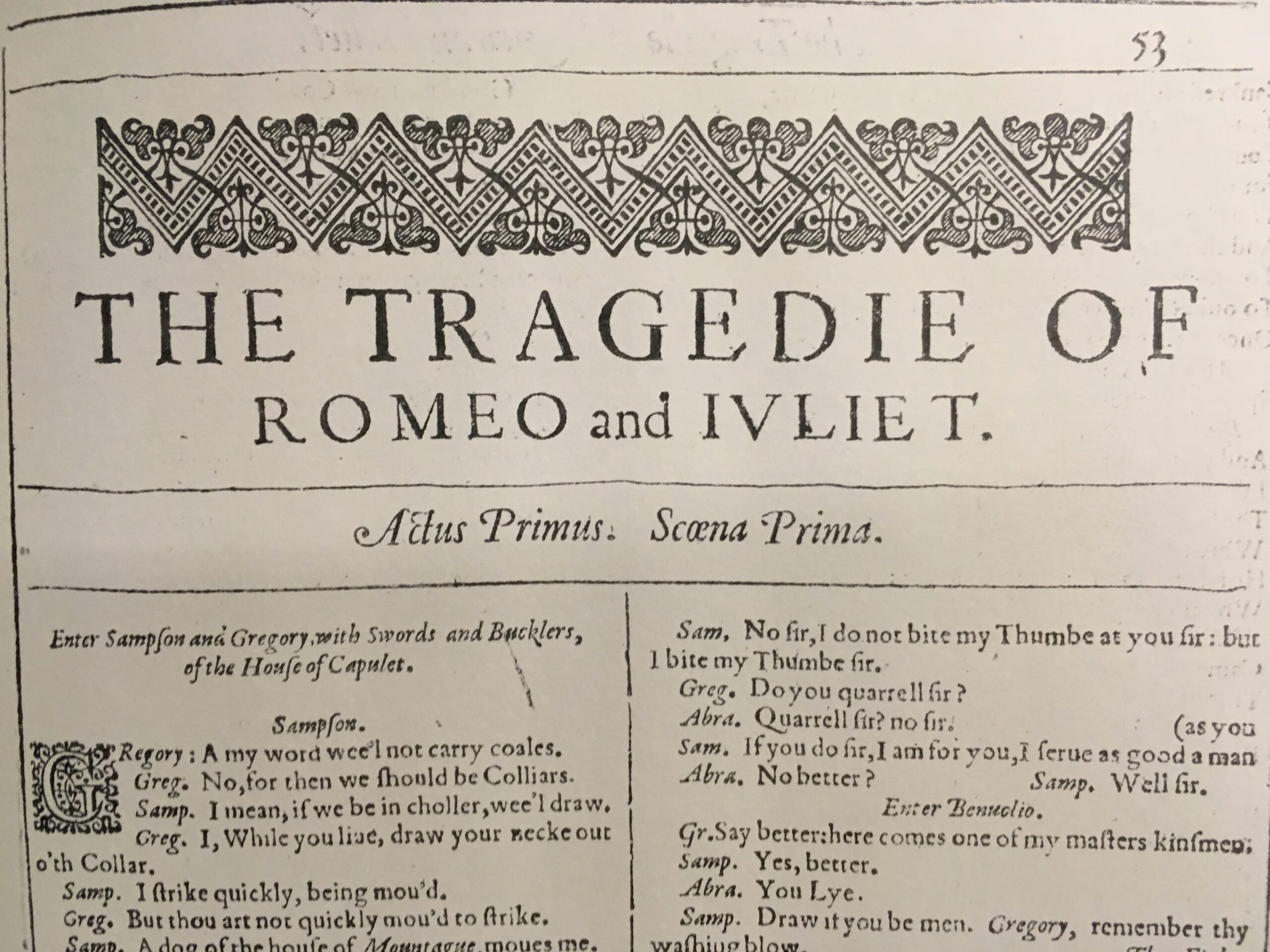

Written in 1595, Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet is perhaps best known for the love-story of its titular characters, and beautiful words of tenderness uttered between them. However, in Shakespeare’s day, it may very likely have been something else that attracted the crowds to The Theatre or Curtain (we don’t know where it was first performed).

In the same way that we flock to the cinema to see the spectacular stunts and special effects in the latest James Bond film or Star Wars, the same could be said for the Elizabethan theatre’s audience, who were drawn by the larger than life spectacle of theatre…and a key ingredient of that spectacle was the violence. Sword fights and associated on-stage physical action staged by the professional artists was a huge draw. Don’t forget that on Bankside, the Globe, Rose, Hope and Swan playhouses all rubbed shoulders with bear- and bull-baiting, cock- and dog-fighting pits. Fencing displays were also staged in the playhouses, and The Theatre was even used to hang a priest in 1588[1].

Consider the first eight plays of Shakespeare’s career –the 3 parts of Henry VI, Richard III and Titus Andronicus are blood-soaked tales, whilst even the comedies of Shrew and Errors have a large amount physical comedy, which at times borders on abuse. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, written in the same year as R&J, opens with a threat of death.

Shakespeare’s society was a violent one. During her reign, Elizabeth I faced down numerous assassination attempts – in fact Shakespeare himself coined the word ‘assassination’ in Richard III. Throughout her reign there was a very real fear from religious fanatics seeking to upturn the established faith, a fever which would culminate 10 years after R&J in the famous Gunpowder Plot. Indeed, she herself wrote to the French Ambassador in December 1583 saying “There are more than two hundred men of all ages who, at the instigation of the Jesuits, conspire to kill me.”

England was almost at constant war – whether it be Spain, France or Ireland. Vagabonds, the ‘thriftless poor’ and decommissioned soldiers, roamed the streets. Liza Picard in Elizabeth’s London, even describes a school for thieves in Billingsgate where you could graduate with the title of ‘judicial nipper’.

Weapons were fairly easy to come by. Most young men, even servants, carried a knife or similar. Picard observes how, if set upon, an apprentice only had to shout “Clubs!” and fellows would come rushing to his aid. In 1592, the Lord Mayor had to travel to Southwark to quell a riot of apprentices from the Feltmakers Guild at a playhouse.

In the year of Romeo & Juliet, London saw the largest riots for 80 years, when 1000 apprentices took to the streets around Tower Hill to protest about social inequality. A curfew was imposed and the theatres closed. The Lord Mayor even requested that the Theatre and Rose playhouses be pulled down[1].

In Shakespeare’s Restless World, Neil MacGregor, examines a rapier and dagger discovered on the foreshore of the Thames at Bankside, which he proposes was dropped by a young gallant, as he climbed in or out of a wherry that would have ferried him across the river for the entertainments on offer. Both weapons are large in size, and incredibly ornate – worn by someone, MacGregor suggests, who wanted to look his best at the theatre, baiting ring or whore house. It illustrates how visible the instruments of violence were, and if carried, one has to assume the intention to use it was also very possible. He also notes that it is in R&J that the term ‘blade’ is used for the first time to describe these stylish, rakish young men.

The Rev. William Harrison in his Description of England (1576) observed that these young blades carry “two daggers or two rapiers in a sheath always about them, wherewith in every drunken fury they are known to work their mischief.”

The Italian Fencing Master Vincentio Saviolo from Padua had recently set up his fencing school in Blackfriars, and in 1594-5 published the first manual on the art of using the rapier and dagger – many of the terms Mercutio mentions in the play can be found in this manual[2]. Given the number of fights in plays, one of the pre-requisites for being an Elizabethan actor was skill in swordsmanship. R&J has three major sword fights, two of them resulting in loss of life.

Actors also seemed to take their “mad blood”, as Benvolio calls it, into the taverns and streets. Actor William Knell was killed after a performance by a sword in the throat in 1587; Christopher Marlowe famously died from an argument over a bill and died from a dagger through the eye in 1593; Ben Jonson, Shakespeare’s friend and rival playwright, actually killed a man in 1598; whilst one William Whyte claimed to have been set upon by four assailants outside the Swan playhouse in 1596, one of them being a Mr William Shakespeare![3]

Being in the audience could be equally dangerous it would seem. In 1587 there was the report of a child and a pregnant woman being shot from the stage, and in 1613 William Bestry was stabbed in a stage fight at The Fortune playhouse.[4]

But the violence in R&J is not only confined to the streets and the young bloods. Indoors there is also the threat of domestic violence. Lord Capulet is particularly visceral in how he will “drag” Juliet on a “hurdle” to her wedding with Paris if he has to. ‘Carting’ was a regular punishment especially for those who had committed infidelity or incest, where you were dragged through the streets for all to see, with a sign announcing the crime tied to you or the horse.

Capulet also comments that his “fingers itch”: a wonderfully written phrase with terrifying connotations. Wife-beating, although illegal and condemned by everyone, was still prevalent in families. In 1589 Simon White admitted he had beaten his wife and “corrected her with a small beechen wand”, whilst the astrologer Simon Forman said of his wife that “she would not be quiet till I gave her 2 or 3 boxes” – as in a boxing of the ears[5].

Mothers and daughters were principally seen as the property of their husbands and fathers, and although his role was primarily to protect and nurture, the way a man conducted himself was largely up to him. Capulet himself says he has worked “tirelessly” in his “care” to ensure Juliet be well “matched”. The vitriolic tirade that pours out of him at her disobedience is truly shocking…but again, possibly not as unusual to the audience as it might seem to us watching today.

Common punishments for breaking the law included standing in the pillory, having your ears cut off or even having them nailed to the pillory. The death penalty could be given for crimes ranging from egg stealing to treason.[6] Given these retributions, Lady Capulet’s fervent desire to seek out one she knows can find Romeo and poison him, is perhaps not such a surprise.

The Friar’s solution to Juliet’s plight even proposes a death-like scenario, whilst Juliet herself in the end commits suicide – something which was abhorred at the time as a crime. Those who took their lives were refused Christian burial, buried outside the city walls, and their family’s honour forever tainted.

R&J on the one hand is a time-less, tragic love story with some of the most exquisite poetry about the tenderness of the heart. On the other hand it typifies the aggressive world in which our heroes not only are pitched against but also what Shakespeare and his audience lived with on a daily basis.

When put together they demonstrate the timeless violence which love causes in its all consuming rage, making us do the rashest of things – and which of us can really deny never feeling that? Perhaps that original blade, Mercutio, sums it up best: “If love be rough with you, be rough with love”

[1] Picard, Elizabeth’s London, Phoenix

[2] Park Honan, Shakespeare: A Life, Oxford

[3] https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/elizabethan-fencing-manual

[4] Neil McGregor, Shakespeare’s Restless World, Penguin

[5] Julian Bowsher, Shakespeare’s Theatreland, Museum of London

[6] Picard

[7] Picard