Tonight we are staging the 4th in our series of ‘rarely-played’ Shakespeare stories, as part of our annual celebrations for Will’s Birthday Bash, so I thought it might be interesting to explore what was going around the time of the writing of this Jacobean tragic-comedy.

A number of clues point us towards the first performance of the play in late 1613, which Simon Trussler describes in the programme/script of the RSC's 1986 production. Firstly, the morris dance in Act 3, Sc 5, eludes to that in The Masque of the Inner Temple and Gray’s Inn by Francis Beaumont, which was first presented before James I on 20 February that year.

Secondly the reference in the Epilogue to ‘our losses’ that ‘fall so thick’ has led many to conjecture a reference to The King’s Men’s loss of The Globe Theatre which burnt down during a performance of Fletcher and Shakespeare’s Henry VIII on 29 June.

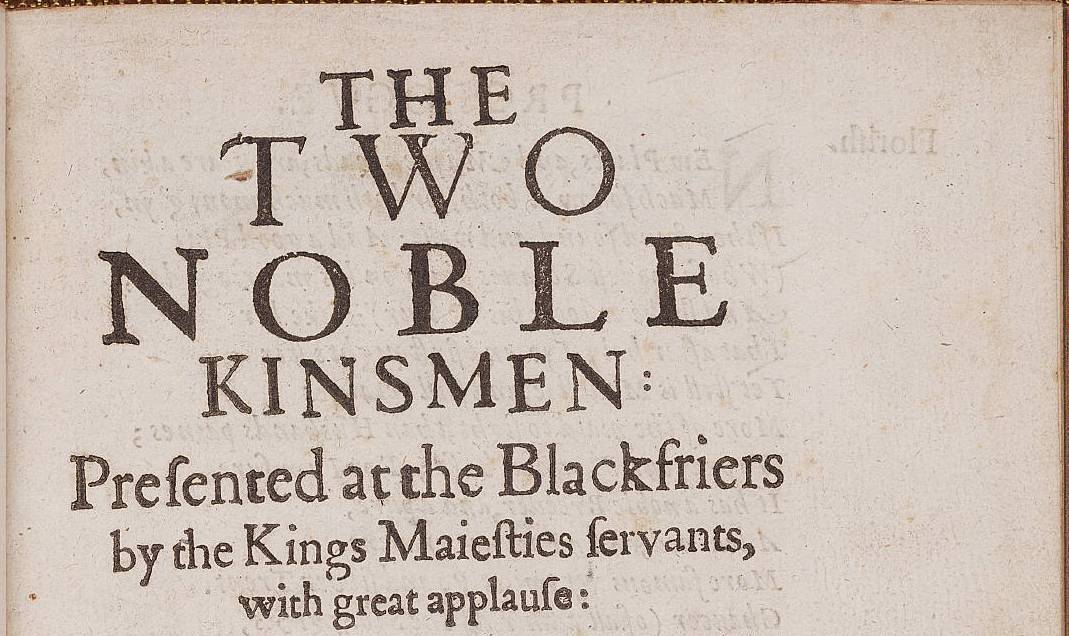

The Blackfriars Playhouse was the King’s Men’s winter home. They first began playing in the venue from 1609, which was on the North side of the river, and was a much more intimate playing space, in which much more scenically could be achieved than in the Globe. You can get a sense of this from the stage directions and the numerous ‘spectacles’ the script calls for:

Music. Enter Hymen with a torch burning, a Boy in a white robe before, singing and strewing flowers. After Hymen, a Nymph encompassed in her tresses, bearing a wheaten garland; then Theseus between two other Nymphs with wheaten chaplets on their heads. Then Hippolyta, the bride, led by Pirithous, and another holding a garland over her head, her tresses likewise hanging. After her, Emilia, holding up her train. Then Artesius and Attendants. Act 1 Sc 1

The Blackfriars was a converted part of the old Dominican Priory located in the West of the City, between Ludgate Hill and the Thames; ticket prices were higher, the clientele more select and, what became the norm in British theatre, end-on-staging. The Two Noble Kinsmen is one of only two surviving plays that we know were written especially for the Blackfriars – the other being Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Maid’s Tragedy (1610).

In 1613 we see Shakespeare doing a number of unusual things, that sadly we have no obvious clues to the motives of.

Firstly he buys a property in the Blackfriars precinct – his only London purchase. This is striking for a number of reasons. Firstly, his work output in London has slowed considerably: his last solo play, The Tempest, had been in 1611, and since the turn of the century he had only been writing one play a year.

Secondly, he had been spending much more time in Stratford in recent years, consolidating his assets there. His brother Richard also passed away in 1613, following the deaths of his other brothers Gilbert in 1612 and Edmund in 1607. We might assume that Edmund’s loss hit Shakespeare pretty hard, as he had followed his eldest brother’s footsteps and become an actor in London. Upon his death Shakespeare paid for the bell’s of St Mary Ovary’s (now Southwark Cathedral) to be rung for his funeral, which was not a cheap request. Edmund is buried in that same church.

Meanwhile, back in Stratford between June and July, his eldest daughter Susannah was accused of adultery with one Rafe Smith, and the case was taken to the Consistory Court at Worcester.

Shakespeare is also absent from the list of sharers in the New Globe upon its reconstruction, so we can assume that he must have relinquished his shares in the playhouse around this time as well. Aside from pointing to a ‘winding down’ of his theatrical involvement this may shed light on his financial status at this point, as he is actually £60 short of £140 needed to buy the Blackfriars Gatehouse. Instead, he engages three trustees to buy it with him: John Jackson (a vintner), John Hemminges (fellow actor) and Will Johnson (owner of the Mermaid Tavern).

This of course raises more questions that it sheds light on, (and there is lots written on the speculation that the Gatehouse was a secret Catholic safe house – but that’s for another time). Park Honan in his biography of Shakespeare, suggests that the purchase is so he can actually be closer to work on his visits to London, and possibly to provide a home for an apprentice writer. Could that apprentice writer then have been John Fletcher, Shakespeare’s collaborator on The Two Noble Kinsmen? We have no record of Fletcher living at the Gatehouse, but he does become the King’s Men’s principal writer once Shakespeare dies. Prof Stanley Wells poses the supposition that from the evidence of Shakespeare’s final plays being much more introverted so the King’s Men called in Fletcher to make them more en vogue, rather than the writer being an apprentice…after all Fletcher is 34 by 1613, and little old to be an apprentice.

We know that Fletcher worked with Shakespeare on three plays, including the lost Cardenio. Born in 1579, he was the son of the Bishop of London, who upon his father’s death in 1596, was raised by his uncle who was a poet and diplomat. Wells identifies him as the 11 year old John Fletcher of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. His first foray into theatre writing did not go well, though Wells points out that a lot of his early work borrows heavily from Shakespeare. Indeed if you look at The Two Noble Kinsmen you will see shadows of Hamlet, Ophelia, Shylock, Dream, Love’s labour’s Lost, As You Like It and perhaps most obviously The Two Gentlemen of Verona – Shakespeare’s first play.

Interestingly, Fletcher pens what is possibly the first true ‘sequel’ (as we know them today). The Woman’s Prize, written in 1605, also went by the name of The Tamer Tamed and picks up a few years after the events of another early Shakespeare play The Taming of the Shrew. Here, Katherina of Shakespeare’s play has died and it is Petruchio who is the subject of the ‘taming’ by his new wife Maria.

Fletcher continued to write for the King’s Men until his death in 1625, and he too is buried in Southwark Cathedral.

When you look at The Two Noble Kinsmen and its many allusions to previous plays of Shakespeare’s, I can’t help but imagine a conversation between him and Fletcher, possibly in the Mermaid Tavern, where the younger man is persuading the old master to write one more play. Fletcher, inspired by the stage hits of the great man, stokes the imagination of Shakespeare with a possible starting point of Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale and maybe Will sees unfinished business in his first play The Two Gentlemen of Verona…and so the pair agree to write the play together, which scholars generally seem to consists of five scenes by Shakespeare, eight by Fletcher and two which they are uncertain about.

In March 1613 Shakespeare is paid 44s in gold to write the Earl of Rutland’s impresa – a motto to adorn a coat of arms - for a ‘show’ tournament at court. Clearly Shakespeare is not afraid to write commercially, and maybe if he needed more cash to pay for a new property in London (and help his daughter fight a libel action back home), perhaps the persuasion to return to his greatest hits was enough to tempt the playwright to put pen to parchment once more…

References

Prof Stanley Wells, Shakespeare & Co., 2006

Park Honan, Shakespeare a Life, 1998

Robert Bearman, Shakespeare's Money, 2016

Simon Trussler, The Two Noble Kinsmen, Metheun/RSC Programme, 1986